WOUNDED WIZARD de M.DIBBLE

Wounded Wizard (huile sur toile) 91,30 x 75,20 cm, 2007.

1) Commentaires en français puis traduits en anglais

2) Comments in French and then translated into English

1) "W ounded Wizard ", cette oeuvre réalisée en 2007 par Matthew Dibble, peintre américain de Cleveland, a de quoi surprendre.

Elle représente un visage humain que l’on pourrait qualifier de " prismatique " puisqu’on a l’impression de le voir à la fois de face et de profil. En effet en se juxtaposant, les deux côtés produisent un étrange effet d’optique comparable à celui d’un prisme.

Par ailleurs le visage qui apparaît sur chaque côté semble être défiguré. A gauche son profil avec un œil, une bouche de travers voire deux et ensuite à droite sa face avec également un œil, un nez et une autre bouche…A l’évidence tout cela provoque un certain trouble : la vision simultanée des deux côtés d’un visage disloqué est particulièrement angoissante d’autant qu’une troisième partie de ce puzzle semble apparaître en dessous des deux autres ?

Par bonheur la tête " unifie " le tout avec un front haut, bombé. L’individu semble être chauve à moins que les deux formes repliées à l’arrière de son crâne ne soient en réalité que les mèches de cheveux qui subsistent encore ?

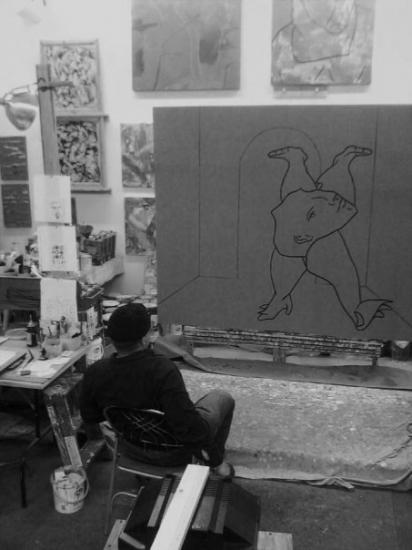

En fait ce personnage étrange n’est pas unique dans l’univers de Matthew Dibble. Cet artiste a depuis des années imaginé et créé par ses dessins et ensuite par ses peintures un panthéon d’êtres monstrueux avec une apparence souvent mi humaine et mi animale dignes de la mythologie antique.

C’est pourquoi l’on peut affirmer que ce peintre de Cleveland continue en quelque sorte l’œuvre des peintres surréalistes du XX° s. A l’exemple d’un Chirico notamment, Matthew Dibble nous montre une œuvre hantée et prophétique où se déploient des forces inquiétantes.

Tout cela signifie l’irruption de l’inconscient qui fait son entrée en scène dans cette peinture. Et Matthew Dibble lui-même conforte cette analyse parlant de son œuvre comme d’une peinture d’ordre psychologique dans un courriel récent du 2/04/2010 : " This painting is psychological… "

Mais ce phénomène n’est pas nouveau puisque Marcel Duchamp voyait déjà en Courbet, le père des nouveaux peintres, l’intervention de la " main subconsciente ". Et bien évidemment aussi chez Matthew Dibble où son travail échappe à la pure raison.

Ainsi dans son oeuvre, le mystère prend corps, grâce à sa façon personnelle de présenter ce visage humain en utilisant les troubles de la perspective ou plutôt en inventant des perspectives nouvelles, dédoublées, multipliées à la façon de ce même Chirico.

Ce faisant, il force les lois de l’art, en donnant une image non pas surhumaine, mais surhumanisée … !

Quant à Chirico pour justifier sa façon de travailler, il n’hésitait pas à dire :

" Il ne faut pas oublier, qu’un tableau doit toujours marquer le reflet d’une sensation profonde, et que profond signifie étrange, et qu’étrange signifie peu connue ou tout à fait inconnue. " (Selon ses écrits pendant son séjour à Paris en 1911-1915)

Afin qu’une œuvre d’art soit vraiment immortelle, il est nécessaire qu’elle aille complètement au-delà des limites humaines. De telle façon, elle s’approchera du rêve et de l’esprit enfantin.

C’est pourquoi comme Chirico, Matthew Dibble ressent de manière similaire ce besoin de dépassement pour échapper à l’angoisse de l’homme moderne ainsi qu’à sa propre angoisse. Et ce désir de dépassement va prendre chez lui les chemins de l’étrangeté par les créatures peuplant son univers.

En cela il est fidèle également à ce que suggérait Nietzsche comme une tension nouvelle de la conscience à l’inconscient :

" Avec la force de son regard intellectuel et de sa vision de lui-même grandissant la distance et, en quelque sorte, l’espace qui s’étend autour de l’homme. Le monde devient alors plus profond, de nouvelles énigmes et de nouvelles images se présentent à la vue. " (Par-delà le Bien et le Mal, I.57)

Peut-être tout ce à quoi l’œil de l’esprit a exercé sa sagacité et sa profondeur n’a été qu’un prétexte à cet exercice, un jeu et un enfantillage. Peut-être, un jour, les idées les plus solennelles, celles qui ont provoqué les plus grandes luttes et les plus grandes souffrances, les idées de " Dieu ", du " péché ", n’auront-elles pour nous pas plus d’importance que les jouets d’enfant et les chagrins d’enfant aux yeux d’un vieillard.

Et peut-être le " vieil homme " a-t-il besoin d’un autre jouet encore et aussi d’un autre chagrin – se sentant encore assez enfant, éternellement enfant !

Ce constat pessimiste de l’homme moderne va le conduire en permanence au dépassement sans le rendre réellement heureux puisque l’angoisse existera toujours. Par conséquent pour vivre tout simplement, il a besoin de s’approcher du rêve et de l’esprit enfantin.

Chez Matthew Dibble cela prendra la forme d’un attrait particulier pour les mythes anciens.

En cela il est aussi le disciple d’un certain Jean Cocteau, le mythographe contemporain le plus célèbre. Celui-ci pour justifier sa passion écrivait sous forme de boutade :

" J’ai toujours préféré la mythologie à l’histoire parce que l’histoire est faite de vérités qui deviennent à la longue des mensonges et que la mythologie est faite de mensonges qui deviennent à la longue des vérités ".

Plus sérieusement Cocteau utilisait les mythes pour l’aider à exprimer souvent les limites de la faculté cognitive de l’homme et notamment du passage du conscient à l’inconscient (l’énigmatique sphinx de Thèbes par exemple).

Mais en réalité ici, faire appel aux mythes et à la mythologie parait moins opérant. En effet l’homme qu’il est donné de voir dans cette oeuvre semble être le peintre lui-même et par conséquent il s’agirait de son propre autoportrait !

D’ailleurs le titre de l’œuvre elle-même " Wounded Wizard " qui peut se traduire en français par " Le magicien blessé " nous donne un premier indice.

Déjà dans le courriel précité, l’artiste nous avait révélé " sa blessure " en parlant de son œuvre. Selon lui, il souffre de ne pas être l’artiste qu’il voudrait être et doute constamment de lui-même et de son œuvre.

Plus loin il est encore plus explicite en parlant d’une peinture d’ordre psychologique, " car moi-même tel que je suis j’ai du mal à me comprendre ".

L’image qu’il nous renvoie dans cette œuvre est donc bien le résultat de l’émergence de son inconscient dans la peinture et par ailleurs les défigurations infligées à son visage vont l’attester plus amplement.

Il est dans la tradition des peintres comme Picasso qui délibérément déformait le visage et le corps de ses personnages dans le seul but de mieux les connaître et les sentir (sic).

Ainsi notamment il peignit Dora Maar en femme qui pleure, défigurée et hystérique pour annoncer une catastrophe ou une situation de désespérance.

D’autres artistes ont travaillé de la même façon : Dali par la déformation pour en faire un symbole surréaliste moqueur et un Francis Bacon qui pour mieux nous faire ressortir la douleur va utiliser la figure comme un matériau brut. Et il va s’en servir en la détruisant à l’extrême pour produire une expression traumatique de l’horreur.

De même les expressionnistes comme Egon Schiele vont aussi déstructurer le corps humain aboutissant à une radicalité expressive parfois extrême (voir son autoportait).

Et sans oublier également De Kooning, qui dans sa série de portraits des Femmes, va utiliser ce même procédé. Son ami Barnett Newman justifiait cette démarche en déclarant en 1962 :

" Les gens peignaient un joli monde mais nous nous sommes aperçu que le monde n’était pas beau. La question, la question morale que nous nous posions chacun – De Kooning, Pollock, moi-même – était de savoir : que fallait-il enjoliver ? "

Fort heureusement Matthew Dibble n’a nullement l’intention d’enjoliver le monde ni d’ailleurs d’occulter son propre tourment.

Son angoisse est perceptible dans cette œuvre et elle est restituée avec beaucoup de sincérité et une grande économie de moyens. Cette oeuvre minimaliste semble plus proche d’un dessin que d’une véritable peinture.

Les trois seules teintes (le blanc, le noir et l’ocre nuancée) ne sont utilisées qu’en arrière-plan et seulement pour colorer le fond de la toile. Seul le trait noir donne vie à ce tableau : véritable poésie plastique restituée en peu de moyens !

Matthew Dibble maîtrise parfaitement le trait et réussit notamment en traçant quelques cernes autour des yeux à créer une atmosphère de profonde inquiétude.

La condensation interne compense cet apparent appauvrissement grâce à ce passage du pinceau qui se veut virtuose.

Les qualités simplicité, précision et lyrisme restituent une image pure et nette…mais tout n’est pas heureusement expliqué et donné dans cette œuvre.

La toile " Wounded Wizard " reste toujours vibrante d’énigmes !

Christian Schmitt, le 5 avril 2010.

2) « Wounded Wizard », this work, produced in 2007 by Matthew Dibble, an American painter from Cleveland, contains element of surprise.

It represents a human face that one could consider "prismatic" since one has the impression of seeing it at the same time straight on as well as in profile. In effect, juxtaposing the two sides produces a strange optical effect comparable to that of a prism.

Moreover, the face which appears on each side seems to be disfigured. On the left, its profile with one eye, a mouth askew, or really showing two, and then on the right a face with another eye, a nose,and another mouth...Obviously, all that indicates a certain discord: the simultaneous vision of two sides of a distorted face is particularly alarming especially because of the third part of this enigma which appears over the other two.

Happily, the head "unifies" the ensemble with a high, rounded forehead. The individual seems to be bald,

unless the two forms protruding behind the skull are in reality , the last two shocks of his remaining hair .

In fact, this strange character is not unique in the world of Matthew Dibble. For years, in his drawings and then in his paintings, this artist has been creating a pantheon of monstrous beings, often with a half-human-half bestial appearance, worthy of ancient mythology.

This is why one can affirm that this painter from Cleveland continues to some extent the work of the twentieth century surrealists . Following the example of Chirico, notably, Matthew Dibble shows us a haunted, foreboding work displaying disturbing forces.

All of that signifies the irruption of the unconscious which makes its theatrical entrance in this painting, and Matthew Dibble himself, supports this analysis by speaking of his work as a psychological painting in a recent email received on April 4, 2010:

"This painting is psychological..."

But this phenomenon is not new, since Marcel Duchamp had seen in Courbet, the father of the modern painters, the intervention of "the subconscious hand" and also quite evidently in the work of Matthew Dibble, where his work escapes pure reason.

Thus in his work, mystery takes shape, thanks to his personal style of presenting the human face by using distorted perspective or rather by inventing new perspectives, split in two or multiplied in the very style of Chirico. In so doing, he forces the laws of art, and offers not a superhuman image, but one which is "super humanized."..!

As for Chirico, in justifying his style of painting, he did not hesitate to say:

"One must not forget that a canvas must always show the reflection of a deep feeling, and that "deep " signifies profound or foreign and that "foreign" signifies little known or completely unknown. In order for a work of art to be truly immortal, it is necessary that it go completely beyond human limits. In this manner it will approach the dream of the childlike spirit." (taken from his writings during a stay in Paris between 1911 and 1915.)

This is why, like Chirico, Matthew Dibble feels the need for going beyond to escape the anguish of modern man as well as to escape his own, personal anguish. This desire for going past the limits is going to take on his part, the road of the unknown through the creatures who populate his universe.

In that, he is also loyal to that which Nietzsche proposed as a new tension of consciousness and the unconscious.:

"With the strength of his intellectual vision and of his view of himself enlarging the distance and to some extent the space which surrounds man, the world becomes more profound; new enigmas and new images present themselves to his view.

Perhaps everything on which the eye of the spirit has exerted its sagacity and its profundity has been nothing but a pretext to this exercise; a game and a childish folly. Perhaps someday, the most solemn ideas, those which have provoked the greatest struggles and the greatest suffering , the ideas of «God» and of « sin » will have for us no more importance than children's toys and and childhood disappointments in the eyes of an old man.

And perhaps this"old man" does he still need another toy and another sorrow - feeling himself still enough of a child, eternally a child!" (Beyond Good and Evil, I.57)

This pessimistic account of modern man will serve to to drive him continuously to go beyond the norm without rendering himself truly happy since anguish will exist forever.

Consequently, to live, quite simply, he needs to come closer to the dreams and the spirit of a child.

On the part of Matthew Dibble, that will take the form of a particular attraction to ancient myths.

In that, he is also the disciple of a certain Jean Cocteau, the most famous contemporary mythographer. In order to justify his passion, Cocteau wrote in the form of witticism:

« I have always preferred mythology to history because history is made up of truths which become untruths in the long run and mythology is made of of untruths which become truths over time».

More seriously, Cocteau often used myths to help him to express the limits of the cognitive faculty of man and notably of the passage from the conscious to the unconscious (the enigmatic Sphinx of Thebes, for example).

But in reality, here, to call upon myths and mythology seems less operant. Indeed the man whom one sees in this work appears to be the painter, himself, and therefore, it would be about his own self-portrait.

Moreover the title, « Wounded Wizard » which can be translated into French as

« Le magicien blessé » gives us a primary indication.

In the aforementioned email, the artist had revealed "his wound " in speaking of his work. According to him, he suffers from not being the artist that he would wish to be and constantly doubts himself and his work.

Furthermore, he is even more explicit in speaking of a painting of a psychological nature.

" I suffer the fact that I'm not the man or artist I could be, that I can always be better."

The image that he sends to us in this work is thus the result of the emergence of his subconscious into the painting. The disfigurement inflicted on its face goes a long way to attest more amply to that.

It is in the tradition of painters like Picasso who deliberately deformed the face and the body of their characters for the single goal of better understanding and feeling (sic) them .

Notably he painted Dora Maar as a woman crying, disfigured and hysterical, to announce a catastrophe or some situation of despair.

Other artists have worked in the same style: Dali by disfiguring in order to make a surrealist symbol of scorn and Francis Bacon who to better emphasize pain and sadness will use the face as a raw material. He will use it by destroying it to the extreme to produce a traumatic expression of horror.

In the same manner, expressionists such as Egon Schiele will also break down the human body leading to an expressive radicalness which is sometimes extreme (see his self-portrait)

And not forgetting also DeKooning,who in his series of portraits of Women uses this same process. His friend Barnett Newman justified this approach by stating n 1962:

"People were painting a pretty world but we realized that the world was not beautiful. The question, the moral question that we each asked ourselves-DeKooning, Pollock, myself-was to find out: What would be necessary to beautify it?"

Very fortunately, Matthew Dibble has no intention of beautifying the world nor of overshadowing his own torment. His anguish is perceptible in this work and it is recreated with much sincerity and a great economy of means. This minimalist work seems closer to a drawing than to a true painting.

The only colors : (white, black and shaded ocher) are used merely in the background and only to color the backdrop of the canvas. Just the black line gives life to this painting: true sculpted poetry recreated in terse, simple means!

Matthew Dibble perfectly masters the use of the line and succeeds particularly in tracing dark circles around the eyes to create a mood of profound concern or worry.

The internal fusion compensates for any apparent minimalism, thanks to the brush stroking which shows itself to be masterful.

The qualities of simplicity, precision, and lyricism, recreate a pure, clean image...but all is happily not explained or put forth in this work.

The painting « Wounded Wizard » still remains radiant with enigma!

Christian Schmitt, April 5, 2010

translation by Darlene L. Nelson

http://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=Partager